Scientists from the University of Washington and a private company are working on a fusion-powered rocket that could slash the estimated four-year round trip from Earth to Mars to a maximum of 90 days.

The technology might also make flights to the red planet affordable -- the launch costs alone of such a manned flight using chemical rocket fuel is about US$12 billion, according to UW.

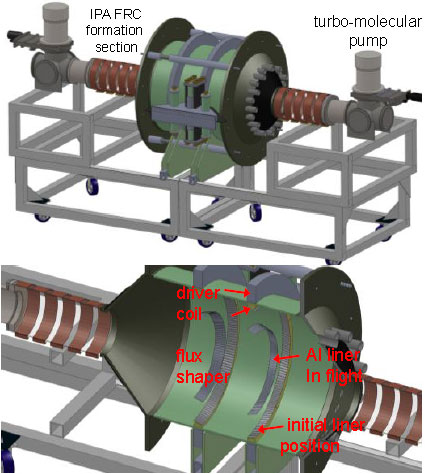

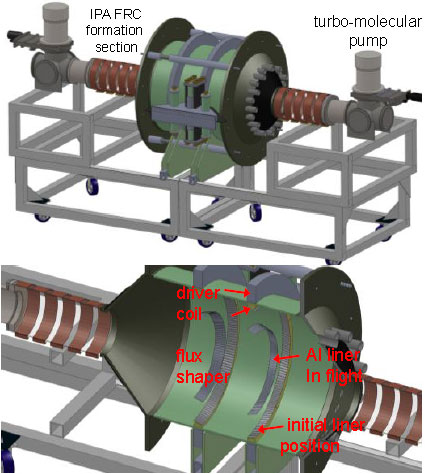

Cutaway Image of Fusion Rocket Design

Cutaway Image of Fusion Rocket Design

The project has received two rounds of funding from NASA's Innovative Advanced Concepts Program. It's led by John Slough, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at UW who is also president and director of research at MSNW, the private company working on the project.

Project Details

The project uses powerful magnets to implode lithium rings, which collapse a conventional deuterium-tritium mix of fusion plasma into a fusion state about once a minute.

Lithium was used because it is the lightest metal, meaning it has the smallest atomic number, Slough told TechNewsWorld. "For a given fusion energy yield, the lightest atoms result in the highest exhaust velocity -- important if you want to go fast."

One set of three rings weighing about 350 gm will be used for each implosion, Slough said. The pressure inside the rings will reach 600,000 atmospheres for a few microseconds, vaporizing the rings. The resulting superheated ionized metal will be ejected out of a divergent magnetic nozzle at high velocity.

Project Details

The project uses powerful magnets to implode lithium rings, which collapse a conventional deuterium-tritium mix of fusion plasma into a fusion state about once a minute.

Lithium was used because it is the lightest metal, meaning it has the smallest atomic number, Slough told TechNewsWorld. "For a given fusion energy yield, the lightest atoms result in the highest exhaust velocity -- important if you want to go fast."

One set of three rings weighing about 350 gm will be used for each implosion, Slough said. The pressure inside the rings will reach 600,000 atmospheres for a few microseconds, vaporizing the rings. The resulting superheated ionized metal will be ejected out of a divergent magnetic nozzle at high velocity.

The magnetic field will peak at about 12 tesla, he said. However, it will not affect the spacecraft's onboard computers because "a thin metal sheet is sufficient to screen out a pulsed magnetic field. The field from MRI magnets is of equivalent strength, and it is on steady state in the presence of very sensitive equipment."

Solar energy will be used to charge the capacitors that generate the magnetic power. "Modern capacitors can easily store two kJ (kilojoules) per kilogram," Slough pointed out. "For two MJ (megajoules) of storage, the cap mass is 1 ton. No big deal on a 134-ton spacecraft."

Volume won't be an issue, as the capacitors have roughly the same density as water -- one ton per cubic meter, he added.

"The propulsion aspects aren't necessarily new," Ben Corbin, a Ph.D. candidate in aeronautics and astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told TechNewsWorld.

Getting to Barsoom

The fusion rocket will be activated for roughly 10 percent of the total trip, split between start-up and braking, Slough said. About 200 gm of plasma would be required to fuel a trip to Mars and back.

Roughly 80 metric tons of lithium rings would also be needed, but storage space won't be an issue because "the propellant amounts to less than 50 percent of the spacecraft mass," he said. "Rocket launches from Earth are typically 98 percent propellant."

NASA's Role in Fusion

Slough's team presented its mission analysis for a trip to Mars -- together with detailed computer modeling and initial experiment results -- to NASA in March. All portions of the process have been tested successfully in the lab, and the team now has to combine all the tests into a final experiment that actually produces fusion using its technology.

NASA's two rounds of funding totaled $600,000, Slough said. A NASA spokesperson was not immediately available to comment for this story.

Slough's project isn't NASA's first involvement in fusion. In June 2011, John Chapman, a physicist and electronics engineer at the agency's Langley Research Center in Virginia, presented his idea for a motor that would extract energy from boron fuel instead of the more regularly used deuterium-tritium mix.

Fusion engines are far more efficient than conventional chemical engines. Other approaches to fusion engines include the Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket (VASIMIR) and the Gasdynamic Mirror Thruster.

Physicists at the University of Alabama in Huntsville are using the Decade Module Two, a pulsed power design used by the U.S. Department of Defense for weapons effects testing in the 1990s. They are trying to fuse lithium and hydrogen atoms and turn some of their mass into pure energy to see whether the theory behind the pulse fusion propulsion model is valid.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Whats On Your Mind??? About This....?